The future of AI is physical

Author: Diego Bermudez, PhD

We talk about “AI” and “the cloud” as if they were ethereal, weightless concepts. Our data, our work, our entertainment, and increasingly, the Artificial Intelligence (AI) that shapes our world, all seem to exist in an abstract digital space.

But they have a physical body, and that body is getting bigger and more resource-hungry every day.

This physical reality exists in hundreds of massive, factory-scale buildings called data centres. While these facilities host the engines of modern society, their rapid growth comes with a staggering environmental footprint. In 2024, data centres accounted for approximately 1.5% of the world’s total electricity consumption. This is projected to more than double by 2030, growing at an annual rate more than four times faster than the combined growth of energy-intensive industries like aluminium, steel, and cement.

This consumption is compounded by aggressive 3–5-year hardware replacement cycles. Valuable, high-performance hardware; often capable of operating for 8-10 years, is discarded prematurely, representing a significant loss of invested capital. Worse, we are failing to recover critical materials from this waste stream. Less than 1% of the global demand for critical raw materials (CRMs) is met by recycling, a figure exacerbated by a global e-waste collection rate of just 22%. In 2022 alone, an estimated USD 91 billion worth of critical minerals were left unrecovered in discarded e-waste.

To address these issues, the DICE network recently organised an expert roundtable to delve into these challenges. The discussion revealed a fundamental conflict between prevailing economic models and the long-term strategic value of circularity.

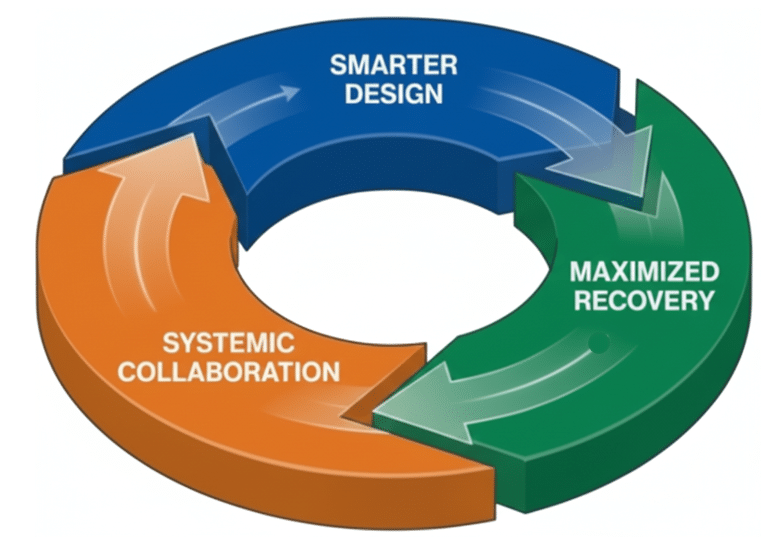

To make the transition to circularity a strategic imperative, we must pull three reinforcing levers:

Lever 1: Design for Value Retention

Building circularity into hardware and infrastructure to maximise lifespan and reuse.

We must prioritise longevity, repairability, upgradability, and material recovery from the outset. Two key actions can drive this shift:

- Embracing open standards (like the Open Compute Project) to ensure interoperability and break vendor lock-in, offering customers flexibility and future-proofed adaptability.

- Designing for disassembly, ensuring components can be easily accessed, repaired, and separated for maximum value recovery at end-of-life.

Lever 2: Operate for Maximum Recovery

Integrating circular business models and transforming end-of-life processes to capture the full value of physical assets.

This lever focuses on prioritising reuse and refurbishment over premature recycling. To succeed, operators must overcome data security concerns through certified sanitisation and encourage OEMs to support the secondary market with accessible parts and qualified repair training.

While hyperscalers like Microsoft and AWS are establishing internal circular centres to achieve high reuse targets, the open market remains fragmented. The next evolution involves innovative business models that decouple revenue from resource use. Examples include:

- Hardware-as-a-Service (HaaS): Incentivising providers to design for longevity.

- Peer-to-peer marketplaces: Increasing hardware utilisation.

- Distributed compute and heat models: Companies, like Heata and Deep Green, turn “waste” heat into a core value proposition by providing hot water to communities.

Germany has already started requiring a minimum 10% Energy Reuse Factor (ERF) for new facilities. However, like the UK, they face public infrastructure readiness challenges that must be tackled as a whole-systems problem.

Lever 3: Collaborate for Systemic Change

Creating the market conditions, policies, and partnerships required for a circular ecosystem.

Grid capacity and e-waste are systemic problems that require coordinated action to overcome barriers like restrictive contracts and fragmented planning. Smart cross-industry policy and procurement are powerful catalysts for this transition.

Mechanisms such as the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), Right to Repair laws, and Digital Product Passports (DPPs) are essential for creating a mandated, scalable circular economy. Simultaneously, governments must lead by example with “Refurb by default” policies and tax incentives to make circular options financially competitive.

Three Key Takeaways from the Roundtable

The roundtable highlighted three insights regarding the barriers we face and the mindset shifts required.

- Economic Barriers are Paramount

While often viewed as an engineering problem, the biggest obstacle to circular data centres is financial. Current business models are built for speed and short-term profit, not resilience.

Most organisations operate on annual CAPEX cycles, prioritising the immediate cost of new deployment over the long-term savings of refurbishment. One industry expert described this as the “sustainability sandwich,” where price drives 95% of purchasing decisions, squeezing sustainability into a mere 5%. For operators, the risk of downtime outweighs the cost of decommissioning, creating a powerful incentive to replace perfectly good equipment. Solutions must therefore move from the engineering department to the boardroom, focusing on tax incentives and procurement standards that reward longevity.

- Design is the Foundational Opportunity, but Maximising Recovery presents an Immediate Solution for Resource Efficiency and Security

There is an insatiable demand fuelling a race to build new capacity at an unprecedented rate. Industry insiders describe this growth-at-all-costs mentality as a “weapons race.”

This rush conflicts with the core circular principle of “resource sufficiency”; using only what is necessary to satisfy demand. The focus is on throughput, leading to the construction of massive new facilities in anticipation of future demand, without considering lower cost existing or serviced capacity. A fundamental problem plaguing the industry as its core components; servers, storage devices, and networking equipment, are not designed to last. Critically, this is intensified by the chase for next-gen AI performance specifications rather than actual functional failure, which accelerates a linear ‘take-make-dispose’ culture where servers are treated as disposable, wasting valuable resources. Furthermore, the supply chain is dangerously concentrated, with over 70% of chip manufacturing located in East Asia, creating geopolitical vulnerability.

- Data Centres Must Be Community Partners, Not Just Warehouses

Data centres are incredibly inefficient regarding energy, with more than 90% of electricity input dissipated as low-grade waste heat. In a circular model, this waste becomes an asset.

“Heat reuse” offers a transformative opportunity to integrate data centres into local communities. Instead of being isolated energy consumers, they can become energy producers for district heating networks or agriculture. As one expert noted:

“We can provide free heat energy to the next user of that energy ‘in the loop’—our output is one of their primary inputs.”

This reframes the data centre’s relationship with its environment from purely extractive to symbiotic. However, in many regions, the infrastructure is not yet ready for this integration, requiring significant investment in municipal heat networks.

Conclusion

To make our digital world sustainable, we must stop treating it as an abstraction and focus on its physical realities.

The blueprint for this transition is built on three interconnected levers: designing for value retention, operating for recovery, and collaborating for systemic change.

This consumption is compounded by aggressive 3–5-year hardware replacement cycles. Valuable, high-performance hardware; often capable of operating for 8-10 years, is discarded prematurely, representing a significant loss of invested capital. Worse, we are failing to recover critical materials from this waste stream. Less than 1% of the global demand for critical raw materials (CRMs) is met by recycling, a figure exacerbated by a global e-waste collection rate of just 22%. In 2022 alone, an estimated USD 91 billion worth of critical minerals were left unrecovered in discarded e-waste.

To address these issues, the DICE network recently organised an expert roundtable to delve into these challenges. The discussion revealed a fundamental conflict between prevailing economic models and the long-term strategic value of circularity.

To make the transition to circularity a strategic imperative, we must pull three reinforcing levers.

A Call to Action

Do you work in this area and would you like to continue this conversation? Get in touch.